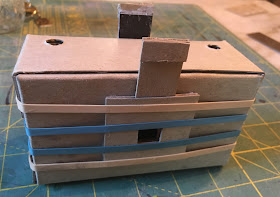

This time trying out the 60mm Cheerios box 120 Populist that was portrayed in the pinhole test photos. I can report that three coats of matte black spray paint is plenty sufficient to make this camera opaque

As you can tell from my profile picture, I'm enough of a nerd (and fan of holidays in general) to feel compelled to bake a pie on Pi Day. In recognition of Isaac Newton's significant work with Pi (although they didn't call it that back then) I chose to make it out of apples. To get as pinholey as possible I piled them into an arrangement, and removed them one at at time as I peeled them, closing the shutter when there was only one left.

This image of the pile of peels looks for all the world to me as though it was done with a large aperture. As this exposure was going on, I was mixing the apples and preparing the pie plate nearby and maybe I bumped the table and the edges of the pile shook more than the center.

I descended into the underworld of Polk Library through this door every day for thirty years. I wonder if I would have remained more sane if I'd worked somewhere with a window. It used to drive me crazy to sit on building planning committees and listen to them insist that it was cruel to make faculty work in an office without windows. The image has got another mysterious impression of limited depth of field. The foreground consists of the eight stairs which at this angle and with their similar concrete grey look more like a gradient of focus.

I started the roll just after I finished the one from my previous batch of studies, turning to the left to the bench where the disk golfers wait for the rest of their foursome to finish. There was about a twenty mile-per-hour sustained wind. Not sure why I got away with the last exposure in the other camera, but the first image on this roll was ruined as I could see the camera vibrate in the wind during the exposure. I used my body as a windbreak for this one and that seems to have worked. Another illusion of large aperture – the muddy foreground and the bench were not affected by the gale but the prairie grass and the trees certainly were. The image is confirmed as pinhole by the clouds which were so distant they didn't move enough during the sunny day exposure to significantly blur and remain sharp.

This building in downtown Oshkosh, designed to give the impression of an old German castle, is known as Pabst Square because it was built to bottle beer in Oshkosh. The beer was brewed in Milwaukee, but refrigeration wasn't sophisticated enough at the time to transport and store bottled beer. They could ship the kegs successfully and bottle just enough to be sold before the beer spoiled. Until the late 1990's, the street in front of it was a railroad track.

I'm not sure what this little building was in the former industrial area next to the river. One of the tricks of the successful photography student is to be inspired by the greats, and this one reminded me of Walker Evans.

We're probably beyond the season of ice and snow, but in Wisconsin you can never tell, so the shovels still stand at attention next to the back door.

The disappearance of the snow has revealed our somewhat cavalier cleaning of the garden last fall.

Arista.edu 100 is slow to start with and has terrible reciprocity characteristics so this interior was about a two hour exposure. If you can stay out of the room, you can photograph what otherwise would be a pretty wiggly subject. Can't quite put my finger on why, but this one reminds me of Clarence White.

All with Artista.edu 100 developed in Caffenol with a .32mm pinhole 6cm from a 6x6cm frame.